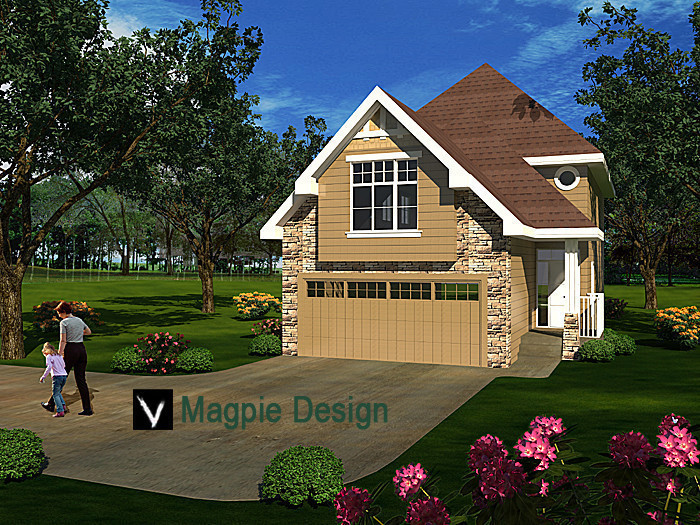

3D rendering

For rendering of 3D scalar fields, see Volume rendering.

Rendering methods

Rendering is the final process of creating the actual 2D image or animation from the prepared scene. This can be compared to taking a photo or filming the scene

after the setup is finished in real life.[1] Several different, and often specialized, rendering methods have been developed. These range from the distinctly non-realistic wireframe rendering

through polygon-based rendering, to more advanced techniques such as: scanline rendering, ray tracing, or radiosity. Rendering may take from fractions of a second to days for a single

image/frame. In general, different methods are better suited for either photorealistic rendering, or real-time rendering.

Real-time

Main article: Real-time computer graphics

A screenshot from Second Life, a 2003 online virtual world which renders frames in real-time

Rendering for interactive media, such as games and simulations, is calculated and displayed in real time, at rates of approximately 20 to 120 frames per second.

In real-time rendering, the goal is to show as much information as possible as the eye can process in a fraction of a second (a.k.a. "in one frame": In the case of a 30 frame-per-second

animation, a frame encompasses one 30th of a second).

The primary goal is to achieve an as high as possible degree of photorealism at an acceptable minimum rendering speed (usually 24 frames per second, as that is

the minimum the human eye needs to see to successfully create the illusion of movement). In fact, exploitations can be applied in the way the eye 'perceives' the world, and as a result, the

final image presented is not necessarily that of the real world, but one close enough for the human eye to tolerate.

Rendering software may simulate such visual effects as lens flares, depth of field or motion blur. These are attempts to simulate visual phenomena resulting from

the optical characteristics of cameras and of the human eye. These effects can lend an element of realism to a scene, even if the effect is merely a simulated artifact of a camera. This is

the basic method employed in games, interactive worlds and VRML.

The rapid increase in computer processing power has allowed a progressively higher degree of realism even for real-time rendering, including techniques such as

HDR rendering. Real-time rendering is often polygonal and aided by the computer's GPU.

Non real-time

Animations for non-interactive media, such as feature films and video, can take much more time to render.[4] Non real-time rendering enables the leveraging of

limited processing power in order to obtain higher image quality. Rendering times for individual frames may vary from a few seconds to several days for complex scenes. Rendered frames are

stored on a hard disk, then transferred to other media such as motion picture film or optical disk. These frames are then displayed sequentially at high frame rates, typically 24, 25, or 30

frames per second (fps), to achieve the illusion of movement.

When the goal is photo-realism, techniques such as ray tracing, path tracing, photon mapping or radiosity are employed. This is the basic method employed in

digital media and artistic works. Techniques have been developed for the purpose of simulating other naturally occurring effects, such as the interaction of light with various forms of

matter. Examples of such techniques include particle systems (which can simulate rain, smoke, or fire), volumetric sampling (to simulate fog, dust and other spatial atmospheric effects),

caustics (to simulate light focusing by uneven light-refracting surfaces, such as the light ripples seen on the bottom of a swimming pool), and subsurface scattering (to simulate light

reflecting inside the volumes of solid objects, such as human skin).

The rendering process is computationally expensive, given the complex variety of physical processes being simulated. Computer processing power has increased

rapidly over the years, allowing for a progressively higher degree of realistic rendering. Film studios that produce computer-generated animations typically make use of a render farm to

generate images in a timely manner. However, falling hardware costs mean that it is entirely possible to create small amounts of 3D animation on a home computer system. The output of the

renderer is often used as only one small part of a completed motion-picture scene. Many layers of material may be rendered separately and integrated into the final shot using compositing

software.

Reflection and shading models

Models of reflection/scattering and shading are used to describe the appearance of a surface. Although these issues may seem like problems all on their own, they

are studied almost exclusively within the context of rendering. Modern 3D computer graphics rely heavily on a simplified reflection model called the Phong reflection model (not to be confused

with Phong shading). In the refraction of light, an important concept is the refractive index; in most 3D programming implementations, the term for this value is "index of refraction"

(usually shortened to IOR).

Shading can be broken down into two different techniques, which are often studied independently:

Surface shading - how light spreads across a surface (mostly used in scanline rendering for real-time 3D rendering in video games)

Reflection/scattering - how light interacts with a surface at a given point (mostly used in ray-traced renders for non real-time photorealistic and artistic 3D

rendering in both CGI still 3D images and CGI non-interactive 3D animations)

Surface shading algorithms

Popular surface shading algorithms in 3D computer graphics include:

Flat shading: a technique that shades each polygon of an object based on the polygon's "normal" and the position and intensity of a light source

Gouraud shading: invented by H. Gouraud in 1971; a fast and resource-conscious vertex shading technique used to simulate smoothly shaded surfaces

Phong shading: invented by Bui Tuong Phong; used to simulate specular highlights and smooth shaded surfaces

Reflection

Reflection or scattering is the relationship between the incoming and outgoing illumination at a given point. Descriptions of scattering are usually given in

terms of a bidirectional scattering distribution function or BSDF.[5]

Shading

Shading addresses how different types of scattering are distributed across the surface (i.e., which scattering function applies where). Descriptions of this kind

are typically expressed with a program called a shader.[6] A simple example of shading is texture mapping, which uses an image to specify the diffuse color at each point on a surface, giving

it more apparent detail.

Some shading techniques include:

Bump mapping: Invented by Jim Blinn, a normal-perturbation technique used to simulate wrinkled surfaces.[7]

Cel shading: A technique used to imitate the look of hand-drawn animation.

Transport

Transport describes how illumination in a scene gets from one place to another. Visibility is a major component of light transport.

Projection

The shaded three-dimensional objects must be flattened so that the display device - namely a monitor - can display it in only two dimensions, this process is

called 3D projection. This is done using projection and, for most applications, perspective projection. The basic idea behind perspective projection is that objects that are further away are

made smaller in relation to those that are closer to the eye. Programs produce perspective by multiplying a dilation constant raised to the power of the negative of the distance from the

observer. A dilation constant of one means that there is no perspective. High dilation constants can cause a "fish-eye" effect in which image distortion begins to occur. Orthographic

projection is used mainly in CAD or CAM applications where scientific modeling requires precise measurements and preservation of the third dimension.

See also

Architectural rendering

Ambient occlusion

Computer vision

Geometry pipeline

Geometry processing

Graphics

Graphics processing unit (GPU)

Graphical output devices

Image processing

Industrial CT scanning

Painter's algorithm

Parallel rendering

Reflection (computer graphics)

SIGGRAPH

Volume rendering